Extreme Acts: The (Ancient) Art of Going Viral

How far would you go for views?

Would you:

🐝 Drink a gallon of honey while covered in bees?

😵 Consume enough Benadryl to cause hallucinations?

🫨 Scream until you pass out while wearing a ski mask?

Personally, I wake up with a healthy dose of fear, so the answer for me is “no”.

But all of these things have been done (and posted on the internet) over the last few years.

New Stage, Same Show

There’s something very human about the desire to cause a spectacle, and it’s nothing new.

Yes, social media has made it easier than ever to know about that one woman who [redacted]. But people have been taking their show on the road since…well, roads were a relatively new thing.

A history of clout-chasing performers

The pursuit of attention is an ancient pastime that dates back to the 5th and 6th centuries.

Motivations vary: Some performers seek fame, while others seek fortune. Almost all of them want followers, whether they’re proliferating an ancient religion or just trying to get to 10k on Instagram. Let’s talk about some of history’s favorite clout-chasers.

423 CE

Simeon the Elder

a pillar of his community

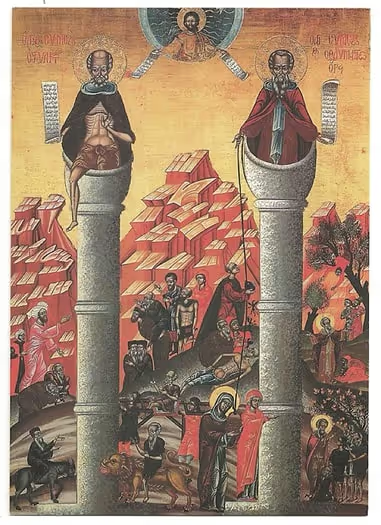

St. Simeon Stylites, a Byzantine monk, popularized the “pillar hermit” lifestyle, an early Christian ascetic practice in which devotees lived atop tall columns to renounce worldly comforts and prove their devotion. Crowds gathered below to gawk, pray, and bring offerings.

Simeon climbed his pillar in Syria in 423 CE and stayed there for the next 36 years, until his death.

1260

Raniero Fasani

whipped his way into people’s hearts

The Blessed Raniero Fasani was the OG flagellant. He began whipping himself publicly after receiving an apparition of the Virgin Mary and St. Bevignate, who told him to start preaching penance for sins. He attracted followers across Italy and Europe, kicking off the flagellant movement.

1487

Lambert Simnel

long lost prince…unless?

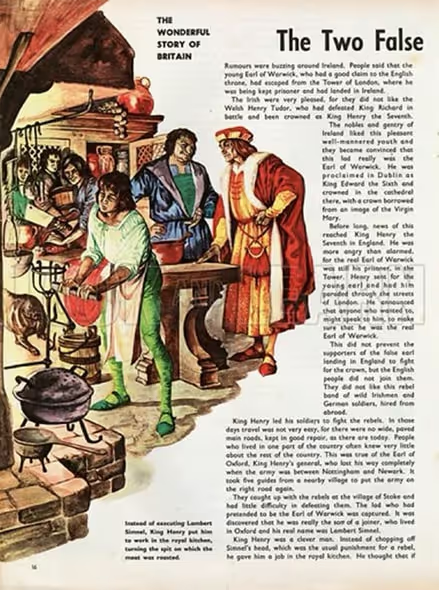

Lambert Simnel was a teenage impostor who nearly scammed his way onto the English throne. Claiming to be Prince Edward, one of the “lost princes in the Tower,” he convinced Yorkist nobles to back his fake coronation in Dublin.

When his attempted rebellion failed, Henry VII — more amused than threatened — pardoned him and gave him a job in the royal kitchens. Could this be the first known case of a failed influencer pivoting to brand work?

1582

Edward Kelley and John Dee

a Renaissance-era collab

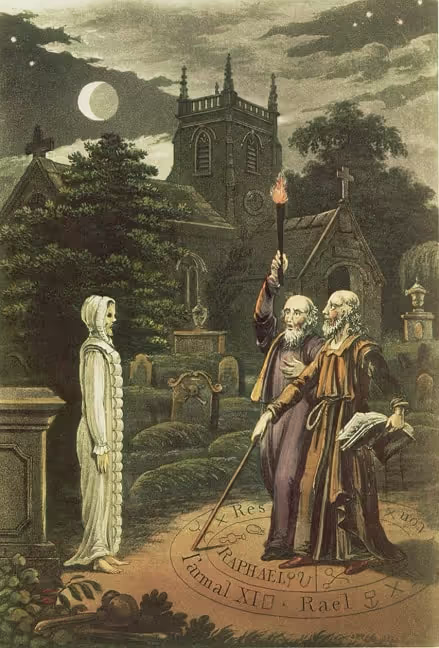

Alchemist Edward Kelley and scholar John Dee were basically the Alex Cooper and Sofia Franklyn of the Renaissance — a high-profile collab fueled by ambition, ego, and “secret knowledge.”

Together, they claimed to speak with angels using a crystal ball, created “Enochian” (an alleged divine language), and pitched their mystical services to Europe’s royals.

Dee fancied himself a scientist. Kelley, more the hype man, promised gold-making and secret wisdom. Like Cooper and Franklyn, their partnership eventually imploded over jealousy, debt, and accusations of fraud.

1750

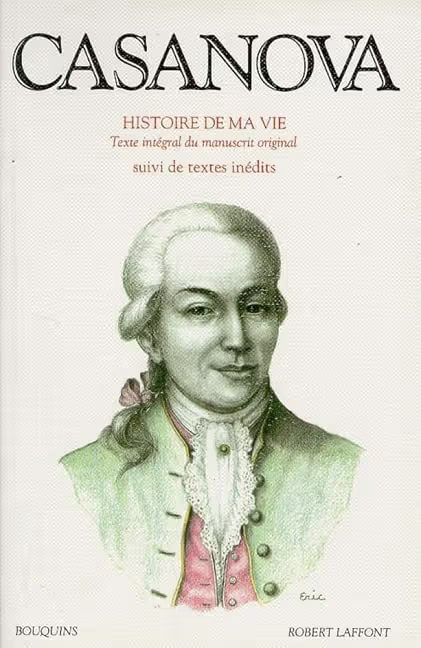

Giacomo Casanova

the original oversharer

Casanova was a Venetian adventurer, gambler, and womanizer who turned his scandalous life into a career. He conned his way into salons and bedrooms across Europe, seducing aristocrats, escaping prisons, and selling himself as a man of mystery.

Late in life, he wrote Histoire de ma vie, a sprawling, self-mythologizing memoir that immortalized his name.

1790

“Mad Jack” Mytton

bored nepo baby

John “Mad Jack” Mytton, an English squire, was so rich and bored that he turned self-endangerment into performance art. He reportedly set his nightshirt on fire to cure hiccups, rode a bear into his dining room to impress guests, and drank several bottles of port a day. Despite burning through his fortune, Mytton became a folk legend for his wild stunts, the Georgian predecessor to Johnny Knoxville and Steve-O.

1801

Joanna Southcott

successful snake oil saleswoman

A Devonshire servant turned prophetess, Joanna Southcott, built a cult-like following by claiming she was the “Woman of the Apocalypse” from the Book of Revelation.

She sold paper “seals of salvation” to tens of thousands of believers, then announced (at 64) that she was pregnant with the Messiah. When the baby never appeared, she died still convinced of her divine calling, leaving behind one of England’s strangest fanbases.

1841

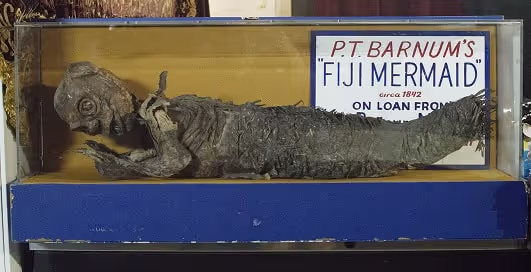

P.T. Barnum

professional bullshitter

Phineas Taylor Barnum, the “Prince of Humbug,” built an empire on hoaxes and hype. He exhibited the “Fiji Mermaid,” promoted General Tom Thumb, and turned deception into an art form.

“There’s a sucker born every minute,” is a quote that has been famously (mis)attributed to Barnum. But, you’ve got to give it to him: He mastered the business of spectacle, turning curiosity and exaggeration into cold, hard cash.

1901

Annie Edson Taylor

do-it-for-the-views daredevil

On her 63rd birthday, school teacher Annie Edson Taylor climbed into an oak barrel and went over Niagara Falls. Her motivation? Fame and fortune.

She emerged alive (the first to survive the feat), only to find that her manager ran off with her barrel and her profits. Annie spent the rest of her life posing for photos and selling autographs near the falls — a good reminder that virality doesn’t always pay the bills.

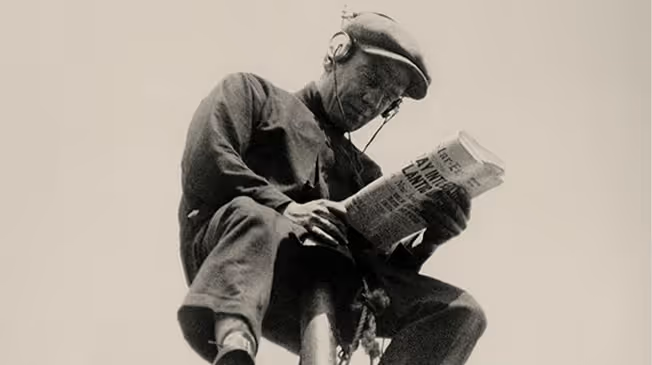

1924

Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly

creator of the viral pole-sitting challenge

Sailor and stuntman Shipwreck Kelly kicked off the pole-sitting craze by perching on a flagpole for 13 hours to win a bet. The stunt drew huge crowds and press coverage, sparking a nationwide fad in which competitors sat on poles for days or even weeks. Kelly later broke his own record by sitting 49 days atop a pole in Atlantic City.

1974

Marina Abramović

pioneer of audience-driven plotlines

Marina Abramović, a Serbian-born performance artist, made endurance and vulnerability her medium. In Rhythm 0, she invited strangers to use 72 objects on her, from feathers to scissors to a loaded gun, and stood motionless for six hours.

Her work tested the limits of audience morality. Today’s shock-collar streamers and no-sleep creators are her digital descendants, turning pain, exhaustion, and total exposure into entertainment.

1999

David Blaine

endurance influencer

Magician-turned-stunt artist David Blaine revived the old-school endurance act for the age of live TV. He was buried alive for a week, frozen in ice for 63 hours, and stood atop a 100-foot pillar in Times Square for 35 hours (very Stylite-coded). His unique flavor of public self-torture made suffering look like art and set the tone for content to come.

2012

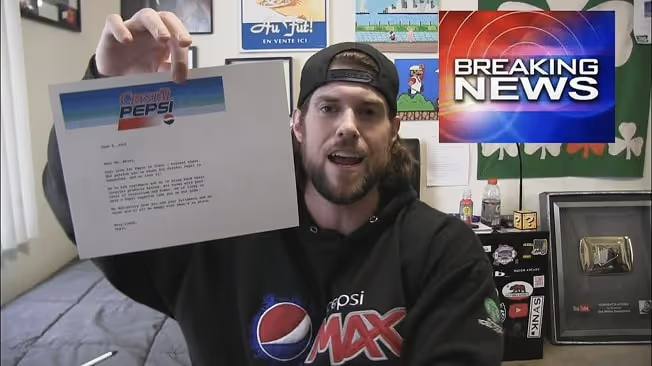

L.A. Beast (Kevin Strahle)

YouTube Gold Era poster child

Kevin Strahle’s YouTube channel gained popularity in 2012 when he began posting food challenges that pushed the boundaries of what anyone should willingly consume. He’s eaten entire cacti, downed gallons of expired milk, chugged hot sauce and cooking oil, and once tried to eat 25 ghost peppers in one sitting.

One of his most notorious stunts was drinking a 20-year-old Crystal Pepsi, vomiting on camera, and then successfully lobbying PepsiCo to bring the drink back (which they did).

2019

MrBeast

stunt philanthropist

Jimmy Donaldson (aka “MrBeast”) kicked off his career by counting to 100,000 on camera. Pretty quickly, his antics escalated. He started giving away cars, houses, islands, and millions of dollars, turning generosity into a YouTube genre. (And even his engagement is fair game for Content.)

MrBeast’s high-production “philanthropy” has drawn criticism for treating charity like content and packaging desperation as entertainment. In 2024, he released a video, Would You Risk Dying for $500,000?, where contestants endured claustrophobic, near-impossible challenges for life-changing cash — almost like a legal version of Squid Game.

2021

Trevor Jacob

crashed out on camera

Former Olympic snowboarder-turned-YouTuber Trevor Jacob staged one of the most infamous viral stunts of the 2020s when he intentionally crashed his plane for views.

In a 2021 video titled I Crashed My Airplane, Jacob parachuted out midflight over California’s Los Padres National Forest, letting the plane go down with cameras rolling.

He later admitted to orchestrating the crash for YouTube clout and pled guilty to obstructing a federal investigation after destroying the wreckage. The video racked up millions of views, proving that an organized disaster is a great way to get clicks (as long as it looks cool in 4K).

2025

Fandy

labor, but make it a live show

Twitch streamer and OnlyFans model Fandy livestreamed her own childbirth for over eight hours. “Water Broke, Baby Time” unfolded in her living room, complete with a birthing tub, midwife(s), and an active live chat. The stream peaked at more than 50,000 viewers, and even Twitch’s CEO dropped into the chat to offer congratulations.

She later insisted the broadcast wasn’t for profit — no subscription pushes or donation goals — and defended the livestream as a deeply personal moment shared with her community. Critics were less forgiving: some called it a boundary-crossing publicity stunt, while others saw it as a harbinger of how little is sacred when life becomes Content.

The Clout Continuum

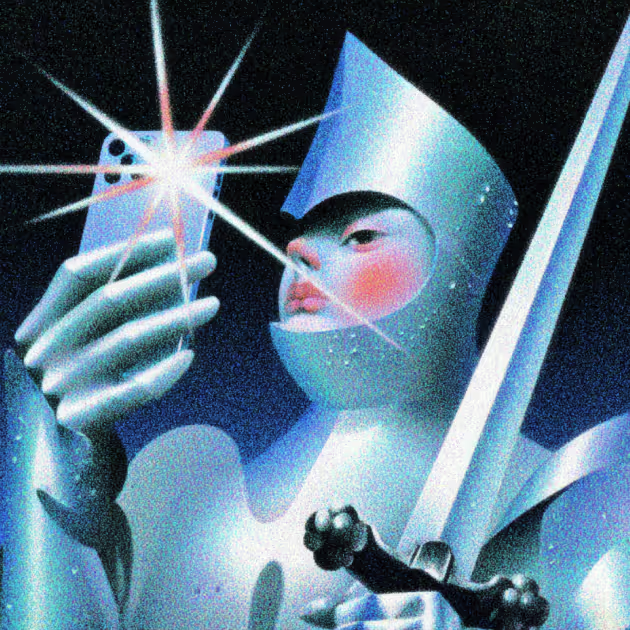

The internet didn’t invent extreme behavior; it just made the audience infinite.

From monks living on pillars thousands of years ago to TikTokers running no-sleep streams today, people have been willing to suffer, sweat, or humiliate themselves if someone’s watching since the dawn of time. It’s an ancient, eternal itch for recognition that must be scratched.

It might feel like creators are going harder than ever today, but that’s just because the tools of spectacle are now in everyone’s pockets. What once required a circus tent or a TV deal now can be done with Wi-Fi and a camera phone.

Instead of rolling our eyes at these big attention grabs, we should recognize them for what they are: modern mythmaking.

It sounds absurd to say that about an OnlyFans model livestreaming her birth or a YouTuber faking a plane crash, but in their own way, they’re continuing a very human story: Every era has its exhibitionists; ours just have better lighting and a bigger audience.

The challenge we face with the next generation of clout chasers isn’t about limits anymore — it’s about knowing what’s real when everything can be faked. PT Barnum had to hire performers; now, anyone can generate a spectacle with a well-written ChatGPT prompt.

In a world where AI can fake the fall, the truly radical act now might be doing something real, and letting it hurt.

© 2026 Manychat, Inc.