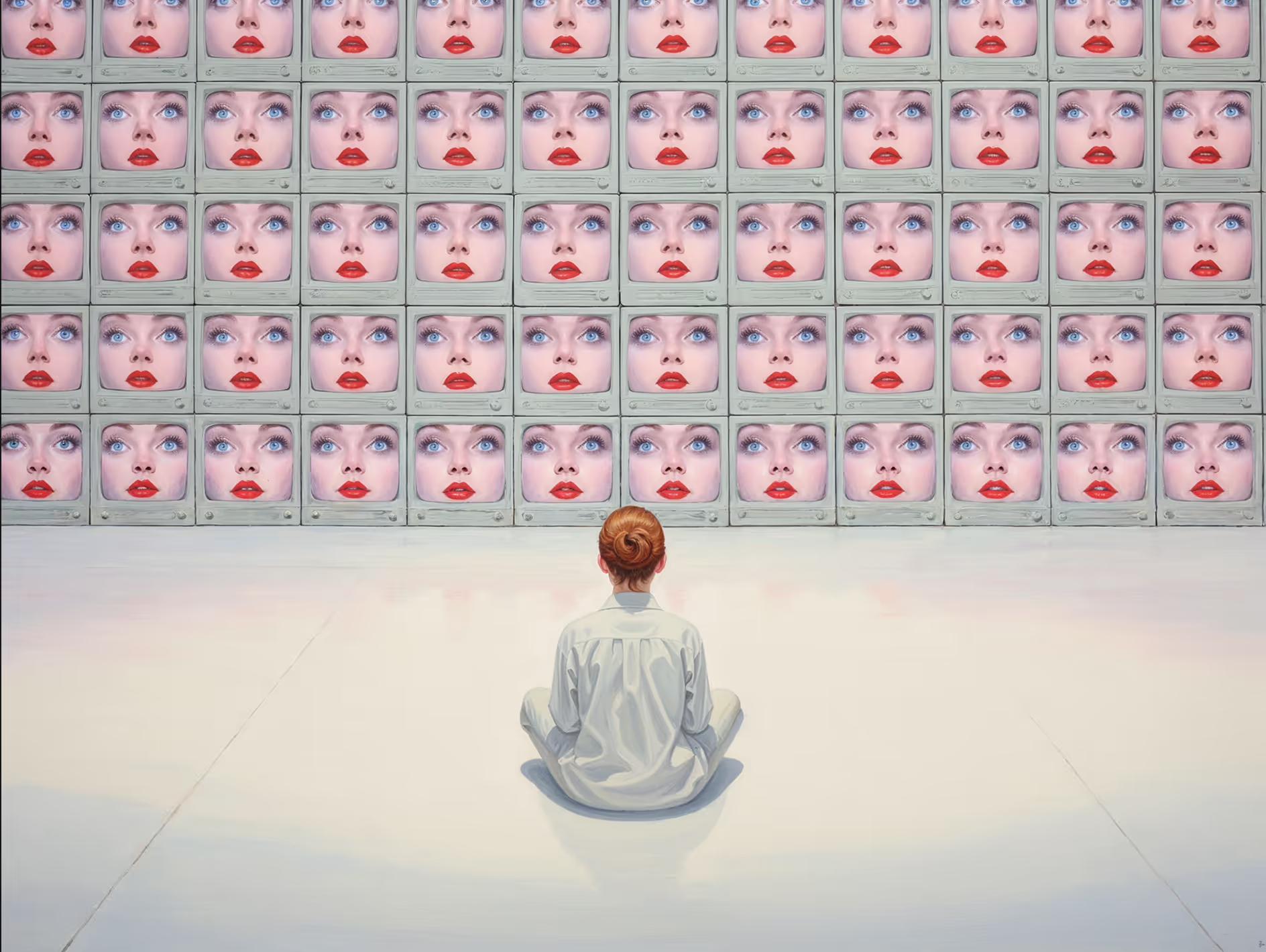

Artificial Exploitation

As if you didn’t have enough to worry about, now your scuzzy ex, bad Tinder date, or even a mad stranger can take completely innocent pics or videos of you, feed them into the correct software, and generate believable fake porn.

What once was a fairly complex process can now be done in your local degenerate’s (mom’s) basement as they sit alone, befunked and untouched by any true, loving human caress.

All the enterprising scumbag needs is the correct AI and some unprotected source material; no actual nudity — or consent — required.

And that should terrify you.

The next frontier of non-consent is AI-generated

This kind of crime is as old as humanity itself. For as long as people have been garbage (forever), predators have fouled the earth, but victimization has taken on new and horrible dimensions with each technological advance. The advent of drawing led to the sharing of exploitative cartoons. Photographs of abuse created cycles of misery. Next, the video camera, and now?

AI.

Celebrities — even historical ones — have been some of the most conspicuous victims, with sexually-explicit and defamatory drawings of Marie Antoinette contributing to her downfall and eventual execution by beheading.

Taylor Swift was famously targeted in 2024, when nonconsensual AI-generated, sexually explicit images of her surfaced on 4chan and the platform formerly known as Twitter. Although the posts were removed, one was reportedly seen over 47 million times before being taken down.

Fueled by a wave of online misogyny, deepfakes have been spreading like wildfires, leaving emotional and reputational devastation in the wake of each attack and leaking into schools, where attacks on students can capture dozens of victims. Abusive material of minors threatens to flood the internet.

(One incident in October 2023, perpetuated by their classmates, involved more than 30 teenage girls at a high school in New Jersey.) No one is safe.

Fake images. Real harm.

And while the content may be fake, the harm is very real.

— Brittany Ratelle, creator attorney.

Ratelle, whose client list includes Cassey Ho, the Bucket List Family, Mary Allyson, and more, has recently traveled the US to speak about some of the challenges creators face in the age of AI. (Ratelle’s recent appearance list included Instagram Summit by Manychat, where her session “Bulletproof Your Creator Business” focused on ways to protect creator IP.) She agreed to speak to Chronically Online Magazine as part of her mission to help equip creators to navigate the legal landscape.

According to her, the threat of deepfakes may affect your bottom lines “especially if you are a public figure and you’re a creator of any type, where obviously there’s a lot that rides on your personal reputation,” Ratelle said. Still, she says public figures aren’t the only people victimized by the nonconsensual distribution of sexualized images.

Do photographs of you exist on the internet? You’re at risk.

Never before has it been so easy or so scalable to commit this kind of crime. Anyone with online images is a potential victim. Anyone with an internet connection is a possible villain.

The spread of technology like face-swapping tools, which let you put a victim’s face on an adult film actor’s body, or apps that purport to “undress” clothed photos, has been made available for free in app stores.

Creating deepfakes used to be much harder, but with new technology, any enterprising creep can easily do what once required a significant amount of digital expertise and access to expensive tools. The barriers to this sort of sleaze are coming down, and we’re all the worse for it.

The Cyber Civil Rights Initiative (CCRI), a US-based organization that advocates for technological, social, and legal innovation to fight online abuse, estimates that 1 in 8 social media users have been targets of nonconsensual distribution of intimate imagery, or NDII, including deepfakes.

And that might be a conservative number.

Dr. Asia Eaton, Head of Research for CCRI, wrote in an email to COM she anticipates this number has increased since the 2017 CCRI study, which included these findings. A new study she co-authored on deepfakes reveals a significant shift in both the accessibility of tools to create deepfakes and the motivation of perpetrators to utilize them.

Eaton said in her new study, the perpetrators repeatedly emphasized how “easy” and “tempting” deepfake tools have become, with some saying they could “literally Google it…put the picture in and it generates itself” and that the process gave them a “little God-like buzz” from seeing what the technology could do.

“When creation becomes effortless, anonymous, and requires no technical skill, prevalence almost always increases,” Eaton said.

Side effects may include depression, anxiety, and more

What is only too easy for perpetrators to make as a joke, clickbait, or in a fit of rage creates serious and lasting harm for victims, Eaton noted.

“My 2024 Analyses of Social Issues & Public Policy article notes that [image-based sexual abuse] can lead to anxiety, depression, PTSD, and social rupture. These are not abstract clinical terms,” she said. “I’ve personally documented how these harms unfold in real people’s lives. In my expert evaluation of a survivor, I observed how the experience of having intimate images nonconsensually distributed derailed her academic performance, ruptured her family relationships, and altered her sense of safety and identity.”

Eaton said the victim told her she was haunted by an ongoing fear of the images resurfacing, saying,

You can’t stop it from happening. You can only react.

It’s nearly impossible to prevent someone from stealing your likeness. Even if you eliminate every image of yourself that you posted, photos on friends’ profiles, employer pages, or even photos you didn’t notice being taken of yourself, all make you susceptible.

And that’s all it takes.

“It’s a good reminder that we should never victim shame, right, and be like, ‘Well, you should have known better to not share that’ [...] That might not have happened,” Ratelle told us.

Francesca Mani was one such victim; she was one of the 30 girls mentioned above in the deepfake attack at a New Jersey high school.

Mani’s story has been well-documented. That October, after learning boys in her class had used AI software to generate fake explicit images of Mani and her female classmates, Mani was called into the principal’s office and told she had been identified as a target.

Using her own experience as fuel, Mani became an advocate for change, testifying before lawmakers that June in support of a new bill: the TAKE IT DOWN Act.

(Due to her tireless advocacy, Mani was named to the TIME 100 Most Influential People in AI list that same year.)

A bill, now a law, requires platforms to TAKE IT DOWN

Previously, AI law in the US was a patchwork of individual state regulations with little federal connective tissue.

The TAKE IT DOWN Act, signed into federal law in May of last year, requires covered platforms to remove nonconsensual intimate images (NCII), including deepfakes, within 48 hours of a victim’s request.

The bill defines “covered platforms” as public websites or applications that provide a forum for user-generated content. These entities must have notice and takedown procedures in place, and they’re required to make “prompt” and “reasonable efforts” to remove copies of the images as well. The Federal Trade Commission was given enforcement authority.

Distribution of NCII is prohibited, with those found guilty of sharing the images facing up to two years’ imprisonment.

Eaton calls the act a “critical step,” but says she thinks it’s not sufficient on its own.

“From both my research and broader international evidence, criminalization and removal requirements help after harm has been done, but they do little to prevent abuse proactively,” Eaton said.

She suggested the following measures to help prevent deepfaking in the first place:

- Promoting app store accountability (requiring Google/Apple to remove or restrict nudifying and deepfake-creation apps);

- Creating upload friction (platforms implementing mandatory AI detection, hash-matching, and dual-party consent attestation before sexual images or altered images can be posted); and

- Levying platform fines modeled after Australia’s eSafety Commissioner, which can compel removal within hours.

Eaton said she believed a multi-layered approach like this is what is needed to actually eradicate the scourge of deepfakes.

Ratelle agreed.

“Especially when we’re dealing with an emergent technology like AI, things are moving so quickly. There definitely will need to be more development in this area.”

Here’s What to Do if You’re Targeted

If you find yourself a victim of NCII abuse, the first step should always be taking screenshots, Ratelle said.

“I know that might be really difficult, so maybe find a trusted friend or someone else who can help you with it. You want to at least have evidence because then you have options [...] depending on what you want in your recovery.”

Ratelle encouraged creators to be aware that what they initially see may not be the extent of a deepfake attack.

“If there’s one [image], there could be others. There could be stills. There could be videos. You can use reverse image search to try to find things.”

After you’ve collected evidence, step two is to request that the material be taken down.

“You would go to the individual platforms and fill out take-down forms and get it [the material] taken down.”

(CCRI has a step-by-step guide to requesting removal of material along with links on its Safety Center page.)

Victims could then seek redress through lawsuits, Ratelle suggested, with several potential rights of action, including “publicity, it could be under a privacy or emotional distress tort, right, saying ‘hey this was an intrusion upon my seclusion, it was intentional infliction of emotional distress, for you to release these images, to create these images using this app,’ or to post it or reproduce it, put it behind a paywall or on X, or whatever the platform is,” she said.

Defamation is also an option.

“This especially could be true if you are a public figure and you’re a creator of any type, where obviously there’s a lot that rides on your personal reputation.”

(Deepfake explicit images represent a thorny new problem creators might not have considered, but as someone who regularly reviews creator contracts, Ratelle noticed a red flag immediately.)

“There is almost always a morals clause in creator deals that says hey, if the creator does anything that harms the brand, if they’re involved in controversy, if they break the law, if they’re caught saying anything incendiary online, we can cancel this contract,” Ratelle warned. “Sometimes, they’ll even have a clawback of money.”

The last step Ratelle suggested was to seek redress under local “revenge porn” laws. (As regulations vary among states, this is where an attorney in your local area can be helpful.)

“That will depend on your jurisdiction for what your options are.”

Survivors Can Seek Support, but Resources Are Scarce

In the U.S., resources for survivors are fragmented and underfunded, according to Eaton. CCRI is one of the most comprehensive survivor-support organizations, but still “many survivors report difficulty finding tailored, trauma-informed, intersectional support — particularly women of color and LGBTQ+ survivors,” she said.

She recommends increasing access to the following based on her own research and experience:

- Trauma-informed mental health care

“Survivors experience PTSD-like symptoms, hypervigilance, and depression; therapy that acknowledges digital trauma is essential.”

- Legal navigation support

“Victims repeatedly tell researchers that existing systems are ‘opaque,’ confusing, or slow.”

- Rapid content removal assistance

“Time-to-takedown dramatically affects trauma severity — swift removal reduces the sense of ‘constancy,’ the feeling that the abuse is permanently embedded in one’s identity.”

- Peer support communities

“Survivor groups reduce shame and isolation and help people understand the abuse as a systemic harm, not a personal failing.”

For now, the onus is still on victims to report NCII, but promising new tools may offer some hope. YouTube has launched an AI-detection tool that uses machine learning to identify potential deepfakes, and other technological advances glimmer on the horizon of the digital landscape.

But until then — stay scared, stay watchful, and lock down your content when you can.

© 2026 Manychat, Inc.